This is the first of what is planned to be an ongoing series of interviews with artists who are bringing attention to the areas, issues, and topics that lie at the heart of GCC’s mission. Whether they are working in the field of visual or applied arts, these artists are creatively addressing the critical issues of our times. If you are an artist—or know of an artist—who is focused on one or more of these issues, please let us know. We would like to highlight this work in future issues of our newsletter and on our website.

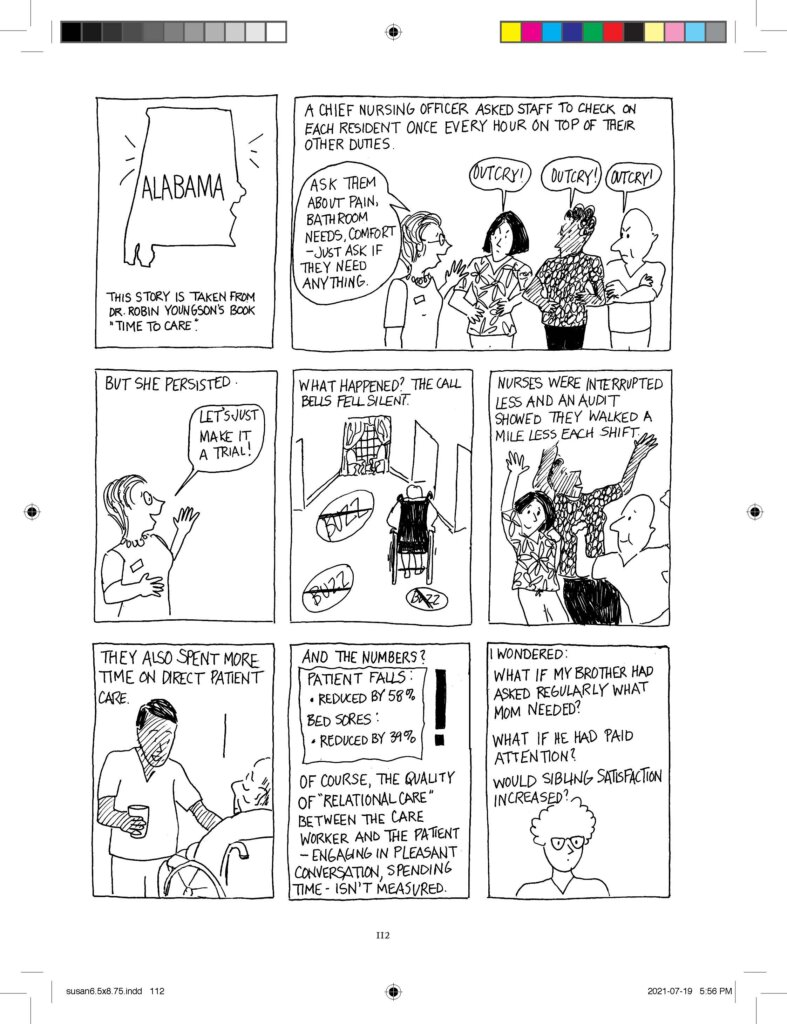

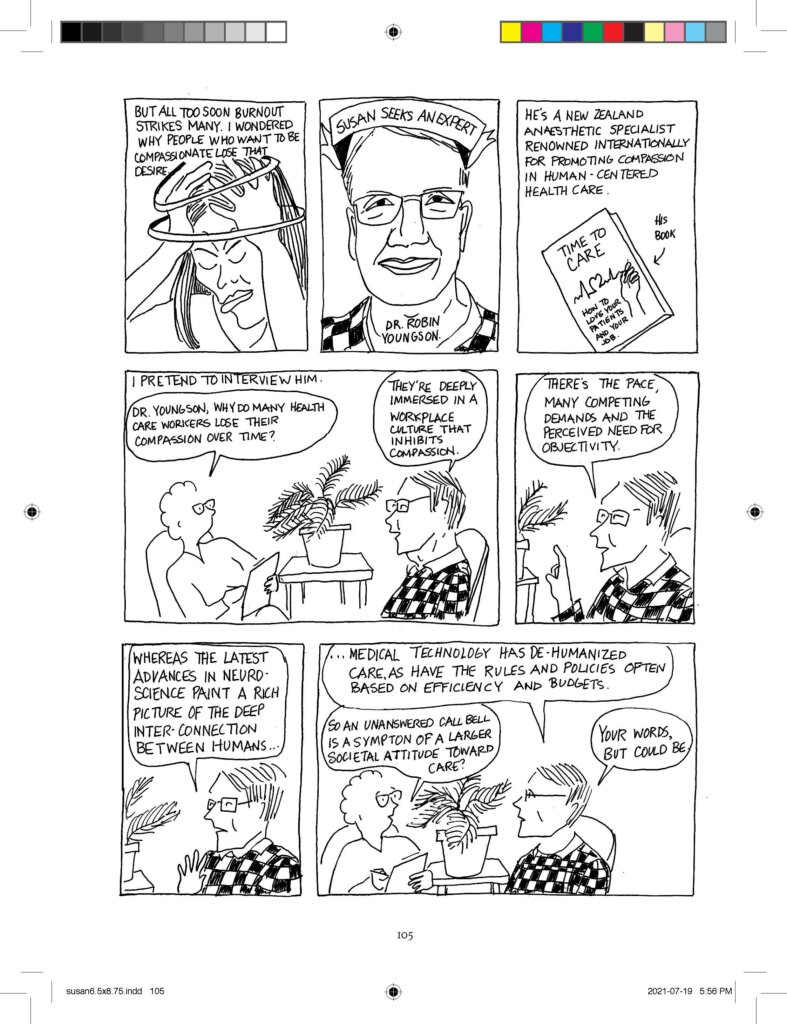

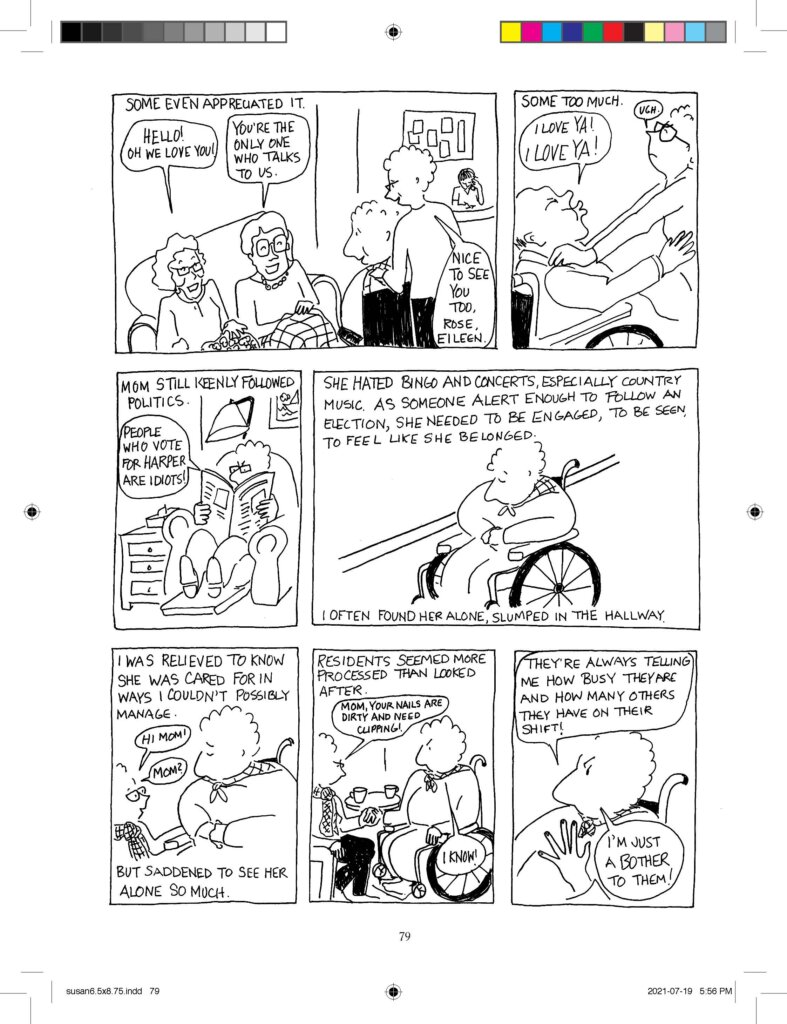

For our first interview I spoke with Susan MacLeod, a Canadian cartoonist, Graphic Recorder, illustrator, and author of Dying for Attention: A Graphic Memoir of Nursing Home Care (Conundrum Press, 2021). She holds undergraduate degrees from Mount Allison and NSCAD Universities, plus a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Nonfiction from University of King’s College. She also completed the Graphic Novel and Visual Narratives residency at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and received a certificate from the Sequential Artists Workshop, a year-long program in Florida.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Ronn Smith (RS): Dying for Attention documents your experience with a faulty healthcare system during the last years of your mother’s life. In it, you deal with a lot of complex and very difficult issues, including ageism, elder care, and death, not to mention mother/daughter and sister/brother relationships. As one reviewer has said, “It’s a handbook for tackling hard things head on, with courage, love, and a strong sense of humour.” Why use cartooning to tell this story?

Susan MacLeod (SM): My mother was in long-term care for nine years. My professional background was public relations, but I didn’t feel I could write about this difficult experience because I had lost my voice and soul to public relations writing.

Graphic Medicine (graphicmedicine.org), which I was aware of at the time, is an association that focuses on the medium of comics and how they intersect with the discourse of healthcare. So I thought, “Let’s see if I can make a graphic memoir of everything I’m going through.” For me, the advantages were that I could skip time, perhaps move around more fluidly than I could in writing. I don’t have evidence for this, but I think images go to a different part of the brain, which might be more emotional. That can be good and bad, because images can be used for propaganda. But in terms of the emotion and the difficulties I was trying to express, that can be done quite easily with a few lines.

Also, this is the book I wanted and didn’t have, so I was writing this for women like me. Men, too, but primarily woman who are going through these difficult experiences with elderly parents. I know these people are exhausted because I was exhausted. When I was a young mother with two toddlers, the only parenting book I could absorb was the one that had cartoons, where every chapter was summarized with cartoons.

RS: In difficult or traumatic situations we often don’t have the time or energy to read books, cover to cover. We need to process information in a very different way in those situations. When was it that you decided you could do this with cartoons?

SM: I don’t think I ever said that I could do this with a cartoon. What I said was, “I wonder if I can do that.” I didn’t know the first thing about the comic world, or the publishing world. But I went to Graphic Medicine conferences and thought: “Let’s take this one step at a time.”

RS: As you write on your website, “[D]rawing, cartooning, and visual storytelling can convey the nuances of various emotional impacts, joyful and painful, to create a direct understanding of difficult life experiences.” Besides Dying for Attention, your website mentions Visualizing End of Life Storytelling and Grief Matters, both of which involve your talents as an illustrator.

SM: Visualizing End of Life Issues (VEOLI) is a group of Graphic Recorders doing what we call Visual Vigils. We originally invited friends and family to gather on Zoom, since this was during Covid, and we asked them a series of questions we had collected from death doulas. We didn’t exactly know how this would go or what it would lead to, but the participants got to think about who they loved, what they loved, and the environment they wanted around them. It was a very friendly way for them to introduce a conversation about dying—plus topics like advance care plans, legacy plans, obituaries, or memorials—to their families.

Grief Matters is a non-profit group led by researchers from University of Waterloo and Dalhousie University. They describe themselves as passionate about raising awareness of grief, with the goal of better supporting grievers, communities, and others. This is called “grief literacy.” Right now, they are working mainly in Nova Scotia but gradually moving into other provinces. It is about bringing individuals together to learn and share knowledge, practices, and experiences about grief. As with VEOLI, it provides an opportunity for me to work as a cartoonist and illustrator. I’m honored to be their volunteer Cartoonist-in-Residence (https://griefmatters.ca/cartoons).

RS: Assuming you have a meditation or contemplative practice, how does it impact your artistic practice, and how does your artistic practice impact your meditation practice?

SM: I don’t think I would have done any of this if I didn’t have a meditation practice. First of all, I’m much braver as a result of the meditation practice. All of that letting go of thoughts. That didn’t come from therapy. And it didn’t come from my nature. It came from my daily meditation practice. I think the meditation practice has also made me more compassionate, which I hope informs the work I do as a cartoonist and artist.

Susan MacLeod, a member of the Global Compassion Coalition, can be reached through her website: www.susanmacleod.ca.

Ronn Smith is a Boston-based writer with a focus on creativity, contemplative practices, and contemporary art.